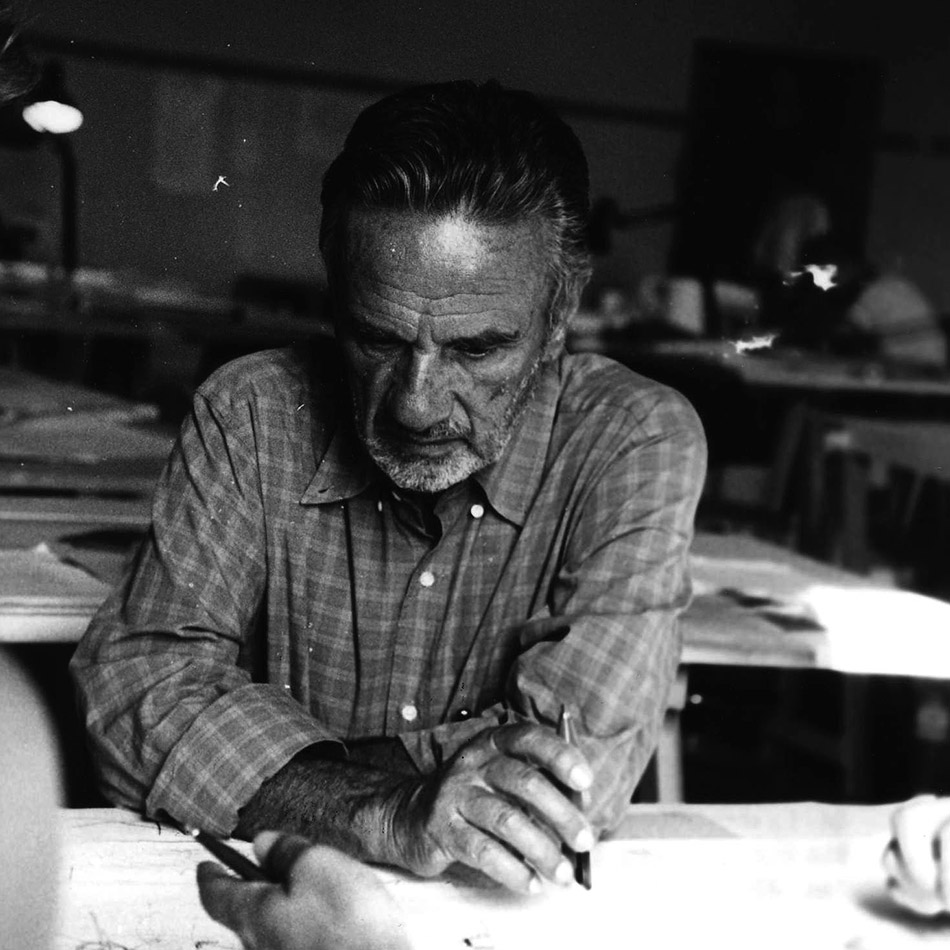

Giancarlo De Carlo for the Benedictine Monastery

It is rare for an architect to get involved in such a complex mixture of architectural emotions

The ‘restoration’ of the Benedictine Monastery lasted more than thirty years. They were necessary to fully understand such a complex and impressive space. The monastery was destined to a new use (it had to host a university faculty) totally different from the original one, later abandoned to devote the monastery to different uses.

The University of Catania invited De Carlo to the Benedictine Monastery in 1980 to get advice on the procedures to follow to restore the building and reuse it as a university complex. Following the visit, the architect suggested the University to launch a national call. But no project satisfied the needs of the building and of the client. In 1983, the University asked De Carlo to prepare a “Progetto Guida” (Guidelines) for the Monastery. Though he had not yet been capable of defining such an unsettling and dark place, De Carlo is triggered to fully understand the ‘spirit of the place’ after meeting three ‘special characters’. ‘They are Giuseppe Garrizzo, Vito LIbrando and Antonino Leonardi: a great historian with a great intellectual energy; an art historian who knew very well the architecture of Catania; and an enthusiast passionate and knowledgeable about the secrets of architectural building and planning’ (G. De Carlo, 1999, our translation).

The restoration of the monastery led to the introduction of contemporary elements that added new strength, a new identity and a new use to the ‘ancient’ ones. The original structure was repaired, brought back to light and made visible to the visitors (travellers, researchers, students). New parts, following the original language, were added. The present dialogues with the past. De Carlo found solutions aiming at the reuse of the spaces, but also at ‘explaining’ the layers, the choices made in the past, even when they were not fully understood. According to De Carlo ‘There is no separation between conservation and planning. It is necessary to wander between tradition and innovation so that stimulus, comparisons, suggestions, interpretations can develop continuously, avoiding that the interest in tradition leads to imitation, and that the interest in innovation leads to superficiality. The project value depends on its capacity to change in order to penetrate the various existing architectonic layers to become a layer itself modifying the meaning of the others’ (G. De Carlo, 1960, our translation).

The architectonic feelings, which the Benedictine Monastery raised in the architect from Genoa, led to the realisation of: the Auditorium (dedicated to Giancarlo De Carlo); the classrooms built in what used to the stables of the monastery; the new, contemporary design of the Novices’ garden with the fountain, the terrace, the helicoidally stairs, the thermal centre built in the lava and covered with glasses and chimney with various shapes; the garden in via Biblioteca; the ‘Bridge-study room’ between the two cloisters. These are all contemporary elements that link the present Monastery and the town, its inhabitants and its history.

De Carlo’s project for the Benedictine Monastery was in the exhibition Des lieux, des hommes held at the Pompidou Centre in Paris in 2004. In 2008, the Sicilian Regional Government declared the value of the monastery as an example of Contemporary Architecture (Opera di Architettura Contemporanea).